Regulate tech and set markets free

The market economy is supposed to set us free. Not only is it supposed to get firms to innovate and lower their prices through a Darwinistic process. It’s supposed to give us the freedom to choose our own products, who to trust and let businesses have alternatives when their partner bullies them. However, all of this only works when there is competition.

Instead, tech firms are creating monopolies in almost every industry. Amazon controls 50% of US online shopping, Google gets 95% of online searches, Uber wants to control taxi markets—Airbnb private lodging, Google and Apple (and Microsoft and Apple) have duopolies in mobile (and desktop) operating systems, and messaging and social media is impossible without using Facebook’s systems.

These platforms and their terms are hard to escape. Consumers can’t choose their messaging app of choice or who to trust with their data, Uber’s contractors can’t negotiate, youtubers must self-censor to appease YouTube’s monetization rules, iOS-developers are banned from making competing products, and developers can’t fight the 30% cut Google, Apple and Amazon take of Google Play, App Store, and Alexa purchases.

They also bar technology progress. Most of us have an NFC-chip which can emulate contactless «chip cards» in our phones, the same technology used in most wireless credit cards, access cards, public transportation cards, wireless keys, and biometric passports. Powered by induction it even works without battery. Yet, we still have wallets because Google and Apple refuse 3rd parties (and other payment providers) to use our NFC-chips.

Innovating?

Many think tech is innovating, but these innovations are usually results of a desperate fear of not controlling the next platform. What happens when the power struggles are settled?

In many areas tech is hardly moving. After internets 30 years bank transfers still take days. Most online banks are a mess. We still use paper receipts and there is no international standard for e-invoices with makes bookkeeping tedious and tax control difficult. Email has not had an update for decades and is so insecure and unreliable (because of spam) that governmental organizations and banks refuse to use them for important documents.

Designers cry inside when they see documents from common word processors like Word and Google Docs. They use second class fonts which are harder to read and show little beauty. And they lack even basic typographic improvements which have been standard in all books for a century like proper justification of text and preventing orphans. The state of the web is not much better. It even lacks multi-columns which could have better filled today’s wide screens. Most documents worth reading are still published in PDFs because there is no widely supported document standard that can adapt to the small screens of laptops, tablets, and phones.

For over 20 years tech-people have dreamed of a world with personal digital certificates. Fully supported this could have solved many of the problems we see today like electronic signing of documents, reliably verify who people are in email and eBay, and get rid of the security mess of having hundreds of accounts on the internet with the same password and usernames you can’t remember. Yet, we still print out documents, sign and scan them.

So why does the problems of tech seem to pile up? Why does not competitors enter to improve the tech giants mediocre products? The problems are many: From networking effects and governments absence at setting standards, but the biggest, and least talked about, is perhaps the problem of zero marginal costs.

The tragedy of zero marginal costs

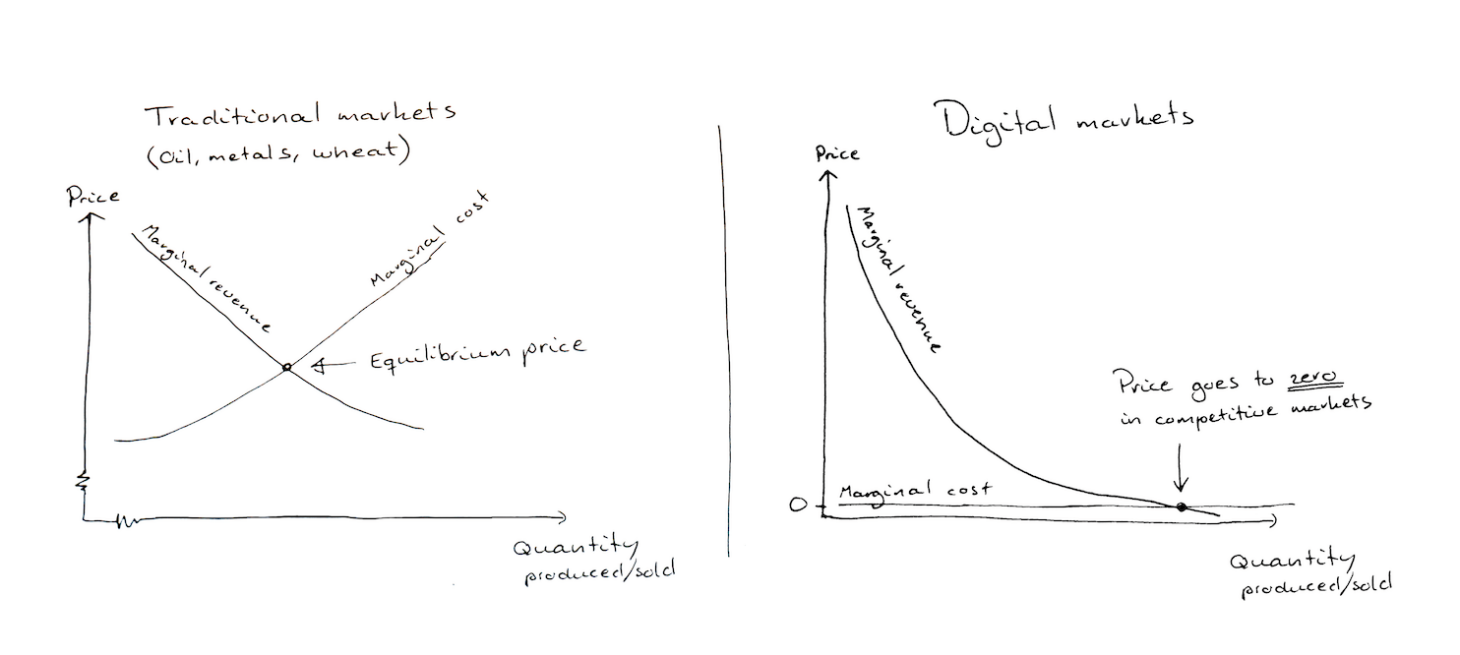

As Joseph Bertrand stated in 1883, prices tend to converge down to near marginal cost in competitive markets. For digital goods, the marginal cost is next to nothing. So for tech, economic forces push the price down to zero—where it is hard to make money. Wired’s then editor-in-chief Chris Anderson called it «the law of gravity online». As a result, most apps are free but have rather lousy quality. While you can spend hours finding a physical notepad with the right paper texture, it is hard to find even a good note taking app that can export notes.

While it might be true that you would spend a few dollars more for quality, it’s easier to get customers to spend $5 more if the alternative cost $30 than if it’s zero. So most users end up with the free version, pushing prices up for the quality version, possibly in an endless death spiral. In my home country Norway, an English–Norwegian dictionary used to cost affordably $30 (for life), now the digital version costs $50 per year because so many use meager alternatives like Google Translate.

The effect of zero marginal costs can be seen on all digitalized goods from books, maps, travel guides, dictionaries, fonts, scientific journals, and newspapers—all have seen a plunge in revenue and quality. While American newspapers had $67 billion in revenues in 2000, their digital part brings in only $4 billion today—weakening democracies in the process.

Since its hard to make money on software directly, software is used to gain power and firms find other revenue streams. Google made Android free to gain control of smartphones and protect its advertisement business. Apple sells hardware by beautiful software (at least in the Steve Jobs era) which locks consumers into its platform. Google gives email, docs, and spreadsheets away for free to gather information for advertisers. Facebook does the same with social apps. These strategies are hard to copy.

In the related hardware industry, which have significant marginal costs, we see little of the same problems. There is an endless variation of phones, cameras, and routers to fit every need. Competitors are often working together for standardization, and standards like 5G are evolving quickly. When Apple surprised everyone with its iPhone in 2007, competitors quickly caught up to prevent market control. This is markets working at their best.

There is an important lesson here: While market economies are usually self-regulating, zero marginal economies, like tech, are not efficient without regulation.

The remedies

The remedies should be clear. As social platforms and public marketplaces like Uber, Airbnb, app stores, ad exchanges—and to a certain degree Amazon—will never have real competitors, they should be regulated as public utilities: run by governmental companies, tendered to the most innovating firm with lowest prices or heavily regulated. After all, it’s how we ended up regulating other natural monopolies like railways, public transit and electric grids a century ago.

Software makers should be required to open their formats and protocols and let competing firms create alternative software. As a start, we should let people have their messaging app of choice—no matter what their friends are using. Only then can we drive innovating and let people choose which provider to trust their data.

Governments should take an active role in developing standards and force all everyone to adopt them. Only then can we improve email and banking where firms have no incentives to collaborate.

Lastly—and this is probably most controversial—governments should probably regulate prices of software. If we want quality, privacy and diversity we need to solve the race to the bottom and forgo free apps. The price does not need to be high—a minimum price of $1 from 1 billion people, or $1000 from 1 million businesses, will not be noticeable in anyone’s pockets. Yet, better software will boost economic growth.

Most importantly, we should embrace regulation. If we value personal liberty we should acknowledge that zero marginal markets, like tech, won’t thrive without it.

©2018 Jon Tingvold, Norway. All rights reserved.

Last updated Feb 7, 2026